Reaction Time - What to Say to Strangers

By Joanne Green

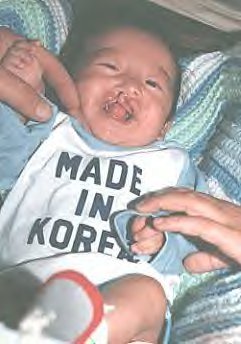

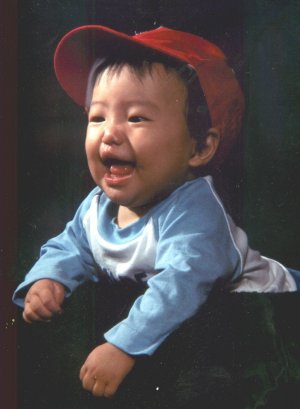

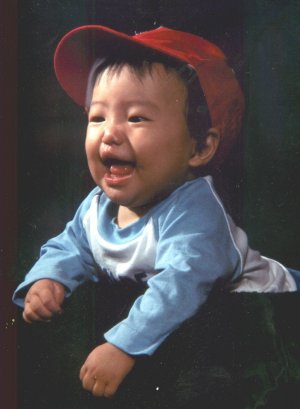

You take your baby with you everywhere. Why? Because you are a proud parent. And because your baby is a part of your life and because you cannot imagine doing otherwise.

Then, when you are standing in line at a grocery store, or while you shop for baby clothes at the department store, or while you sit at a park bench rest your feet, or at any other time when you least expect it, a stranger walks up to you and says, "What on earth happened to your baby's lip? What did you do to cause that?"

It's painful. It cuts to the core of our existence - our very heart. There is so much in that one question - so much rejection, repulsion and blame. And so much of it unfair.

How do you respond? It hits you so fast and so hard, it is difficult to respond at all. Your cheeks burn. Your eyes well up with tears. You are rendered speechless and you incredibly find yourself apologizing. Then, long after the stranger has left to go on back to her own life, you think of a dozen better things you could have said. And you go on after than thinking about how you could have handled the situation differently.

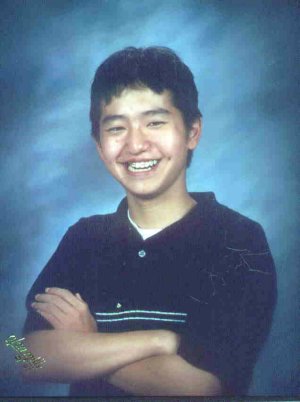

It is a normal scenario. We have various response knee-jerk reactions. But in the final analysis, what does it matter how we reacted? We would never see that stranger again. The stranger would forget the experience in a week, if not sooner. But there is one person present who will remember the experience - at least on some level - for a very long time to come - - your child.

How you respond to a situation involving your child's cleft and the perception of it by others helps to define the cleft in your child's mind. If you respond angrily, lashing back at the rude intruder, it may vent some of your frustration, and it may teach the stranger to be more careful the next time, but it will teach your child that the cleft is a threat and a target for ridicule.

"How dare you say such a thing!?" says to your baby, "we have been attacked. It's time now to assume our defensive posture." And the most logical conclusion your naturally egocentric child can draw is, "If there were no cleft, my mommy would not be mad - - if there were no me, my mommy would not be mad."

You might instead deny the existence of the cleft altogether. "There's nothing wrong with him. Please do not ask such rude questions." But your child knows there is something "wrong." He knows he has a cleft - or a cleft scar. Even very young children are aware of differences between themselves and others. By denying the fact of the cleft - or its importance in your child's life - then he assumes that the cleft is something to be hidden and kept secret. The only reason why that makes sense to him is that the cleft - therefore the child - is a source of embarrassment to the parent.

Or you might cry. It's hard not to cry when your child has been attacked. It's hard not to feel the pain of someone's accusation - especially when you know it is untrue, but a part of you still feels that it's not. All of your old pain comes flooding back, along with the new pain of knowing your child will feel the pain too.

If you cry, you usually wait to cry later. The stranger is gone. She does not know how much she hurt you. But your child is still there. Your child sees your pain, and your child senses that the pain has something to do with him, The message? "The cleft is a tragedy. I make my mommy cry."

Each of the above reactions is natural and understandable. But each one teaches something negative to your child.

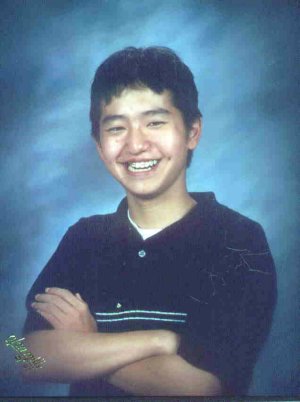

Empirical research has strongly supported the notion that a parent's attitude toward a child's birth defect is the single strongest indicator as to how well the child will adjust. Parents who had healthy attitudes toward their child's cleft had children with a strong positive sense of self. It is no coincidence.

If you convince your child that you love him, then he sees himself as lovable. Even if your love is unconditional. If you cannot deal with any aspect of your child, then that aspect becomes his millstone.

When confronted with a rude comment or remark, the answer you give to the person speaking to you is not nearly as important as the message you give your child.

Answer calmly, assuredly, maybe even educationally. Tell the person who made the comment, "My son was born with a cleft lip and palate. Nobody really understands what causes a cleft, but they do know that it is not caused by the mother. It just happened and we are dealing with the reconstructive process."

That answer tells you child that he is a child first, and that the cleft he was born with does not cloud her perception of you as a person. The cleft is a simple fact of your life- something you can handle while you love your child.

Or you may choose to use humor.

"What? Something wrong? I don't believe it! How could I not have noticed this before?!" And the rude person gets the message ("this is none of your business, really") and mom and child do a couple of mental Hi-Fives in the air. Your child sees you as the conquering hero - the one in his corner, and adequate to the task. His champion. And you laugh together.

Most of the time strangers who approach are not trying to make us feel bad. They simply lack the social grace it takes to tell the difference between things that are their business and things that are not. And, having decided that they have some kind of right to another person's personal information, they fail to stop and consider the impact their harsh words will have on you or your child.

That person is not important. Your child is. React for your child.

--------------------------------------Joanne Green is the mother of three children born with clefts. She is also the Editor of WIDE SMILES Magazine.

(c) 1996 Wide Smiles

This Document is from WideSmiles Website - www.widesmiles.org

Reprint in whole or in part, with out written permission from Wide Smiles

is prohibited. Email: widesmiles@aol.com

Questions? Comments? Contact Merribuck@aol.com