LOST AND FOUND

by Joanne Green

Nine months is a long time to wait. It's especially long when what you are waiting for is your heart's desire. But nature dictates that we have to wait. And so we spend the long waiting months by dreaming and preparing for the child that is to be.

Meanwhile we have the hopeful assurance that all is going to turn out well. We visit our Ob-Gyn and he listens and pokes and measures and smiles. He tells us that all is "progressing well." We watch the fuzzy pictures of a living child on the monitor of the sonogram and hope to learn if it's a "he" or a "she". But the lively little lump squirming on the screen assures us that all is indeed well. We watch our bellies bloat and we feel the thumpings of life within. We rub the bump where the head should be and tell ourselves that all is well. And even though occasional doubts pester us, we know that everything is as it should be. All mothers-to-be worry, don't they?

While we waited we prepared. We prepared a bassinet with soft colors and muted tones. We pictured our sweet baby's head resting gently on the pillow. We collected a layette, fingering each little piece, smelling each new scent. Our baby would be so cute - so loved. We stood in the empty, waiting nursery, arms caressing the lump of our own flesh that itself caressed our baby, and we waited.

Fantasy plays a major role in preparation. We cannot prepare for any event unless we can fantasize that event happening. Fantasizing our baby was easy. We talked about our baby to every important person in our lives, and even some who were not so important. We tried out dozens of names until we found the one that perfectly suited the child we imagined ourselves to have. We sat in our rocker and imagined ourselves holding a bundle of pure treasure and singing sweet lullabies to hasten a peaceful sleep. We communed with our babies in fantasy long before our babies could accept that communion.

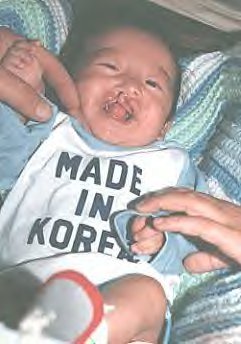

We pictured our babies in our arms. We pictured them big and healthy one day, small and vulnerable the next. We pictured heads full of hair, and we pictured heads of soft down. We saw a boy, then we saw a girl. But we never saw a cleft. That is, not until the morning she was delivered.

Suddenly the picture of that imagined baby was shattered. She was gone. The pink little face that we gazed upon so lovingly in our fantasy was marred by an open hole where the perfect rosebud lips should be. The delivery did not go as we had imagined it would. There were hushed tones in the delivery room. The baby was rushed passed us. Something was said about a birth defect. But this was not the way it was planned. Our husbands and we were going to share this experience. It was going to be so beautiful. But it's confusing. And what did they say about a birth defect? When we saw our baby for the first time we weren't prepared. We had never seen a cleft before. What were those feelings we felt? They were so mixed. We asked ourselves, "Is this what they mean by a 'face only a mother could love'?" And we have to admit that there were times right at first that we wondered if even a mother could love that face.

Our culture dictates that there has to be an instant, magical bond that forms between mother and child. Why wasn't it there? What would all this mean? Could we even breastfeed our child? Will she live? If she does live, how could that "thing" be repaired? Why, oh why, had this happened to us? Were there feelings you felt that you could not admit to, even to your own mother? Did you feel cheated? Ashamed? Angry? Unable to love even your own child? We don't feel them all, but we would not be normal if we didn't feel some of them. What we felt was grief. We lost the fantasy child. In its place was a child we never imagined. It's not the same as losing the boy we envisioned when "he" turned out to be a "she". Suddenly pink becomes the most beautiful color in the world. But we lost the "normal" child we assumed we would have. And in its place we have a child that we do not fully understand.

How can you grieve the loss of something you never had, or someone who never really existed? Simply, you did have it in your heart. She did exist to you. That normal, healthy baby was as real to you as anyone else in your life. You not only now must grieve the passing of that child, you must somehow deal with the concept that she was never real to begin with. It is more than a loss. It is almost a retroactive loss. you not only lost her - you never had her in the first place. There is an emptiness left that can only be described as a hole. And the child in your arms may not fill that hole right away.

Grief takes many forms. At first you may want to deny it all. Denial is funny. It is like anesthetized reality. With the help of denial you can look squarely at something difficult and not be hurt by it. You may wake up and think you dreamed it all. Or you may tell yourself (facts to the contrary - but that never dissuades denial) that it will somehow "go away" all by itself. You can deny that it makes any difference. You may hold tightly to your child and confront the world, daring anyone to even suggest that you feel anything but love for the child with the deformity (and still, in the recesses of your heart you wonder if you will ever be found out).

Denial gives way to anger. You may feel angry at the doctor for having done something wrong, or for not having warned you of every possible inevitability. Or you may just be angry at the doctor for the way he handled the delivery. You may be angry at your husband, After all, it must have come from his side! Why hadn't he told you that he carried defective genes? Or you may simply feel that your husband doesn't feel the way you think he should feel - not sorry enough, not loving enough, not sensitive enough to what you are feeling. You may be angry with the baby. After all, there is only one thing you asked of your child - to be born healthy. And she wasn't. As ridiculous as your anger may seem, it's there. You are even angry at yourself.

Anger turned inward becomes guilt. Grief causes you to feel guilty. You wonder what you did during your pregnancy that could have caused this. Your mind wanders to every tiny indiscretion. A friend smoked in front of you once. You drank coffee in the early days of your pregnancy. You took medicine for your morning sickness. Whether or not your self-blame is groundless (and it usually is), you feel somehow that that is what made the difference, and you are to blame. You may blame yourself for thinking bad thoughts, or for watching a horror film during pregnancy, as though it somehow "marked" your baby. Or you may have remembered some particular sin in your past that has come back to haunt you, and your child's deformity is somehow God's punishment for the awful thing you did. Or you may search your childhood to think of anything you may have done that could have damaged your chromosomes. At any rate, you try to shoulder the guilt. After all, you were entrusted with the task of carrying this child. And somehow you did it all wrong.

Guilt leads to shame. You begin to find it difficult to talk to others about your child's condition without becoming defensive. You sense that everyone else in your life is disappointed in you for producing a less-than-normal child and you wonder how you will make it up to them.

Denial, Anger, Guilt, Shame. These are not the feelings of motherhood, are they? Actually, yes, they are. They are the feelings of grief, and from time to time every mother experiences some form of grief. But for you it came early, while you were defining your role as a mother. It may help to realize that you grieve because you love. If it meant little to you, you would never have grieved the loss of it.

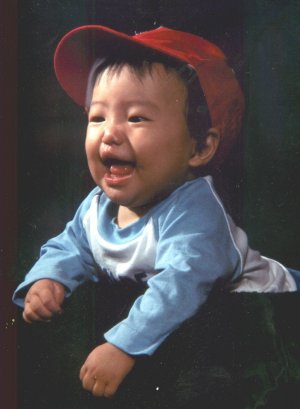

But grief leads finally to resolution. One day you are holding your child and gazing into her sleeping face, and you realize that this is the little face you love. At that point you become ready to put aside that which was lost so you might fully embrace that which you now have found - the child in your arms.

You learn that you have grown to love your baby as she is, not as you had hoped her to be. And you know that your love for her is as strong as any love shared between mother and child could be. You do not love her in spite of the deformity, or aside from the deformity. You love her as she is. You will deal with the deformity.

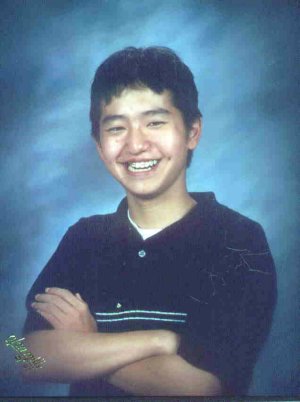

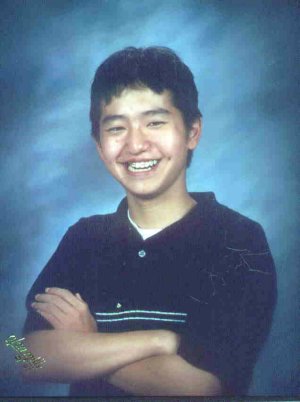

You find strength born of the love that you share with your child that helps you to deal with all that is necessary to insure her of a normal future. You find yourself able to look at your child's face and see a child, not a cleft. Your child ceases to be defined by her deformity any longer. You have reached resolution.

It is okay to grieve. In fact, it is necessary to grieve. The loss is real, even though what was lost was only imagined. It is only by grieving that you can eventually let go. It is only by letting go of what is lost that you can embrace that which was found.

Grief can take only minutes or hours, or it can take months. If you find it difficult to move through the various stages of grief, go to a counselor. You are only experiencing a temporary problem and you may need help to get over it. In most cases, the stages of grief will return from time to time - even years afterward. As long as your grief does not interfere with your relationship with your child or your ability to be an effective parent it is normal. If that is affected, help is available. Speak to your craniofacial team or medical professional. You are as much their concern as your child is.

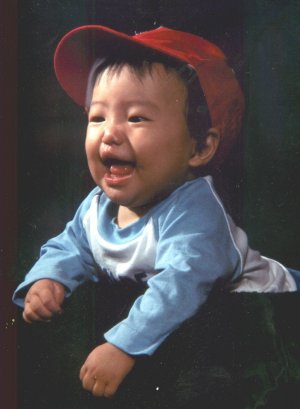

On the day your child was born, something was lost, and something was found. Concentrate on that which you have. And congratulations. You have a beautiful baby.

--------------------------------------Joanne Green is the mother of three children born with clefts. She is also the Editor of WIDE SMILES Magazine.

(c) 1996 Wide Smiles

This Document is from WideSmiles Website - www.widesmiles.org

Reprint in whole or in part, with out written permission from Wide Smiles

is prohibited. Email: widesmiles@aol.com

Questions? Comments? Contact Merribuck@aol.com